|

|

|

|

The

Matrix

|

|

|

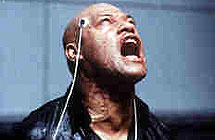

"Welcome to the desert of the real." Any viewer who doubts that cyber-guru Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne) is quoting the postmodern French philosopher Jean Baudrillard at a central, spectacular highpoint of The Matrix has obviously missed the moment earlier in the film when Neo (Keanu Reeves) dives into his copy of Simulacra and Simulation – pointedly turned to the chapter "On Nihilism". So what? For some spectators this will be a passé, corny reference, to others it will be hopelessly esoteric. But the secret of this film's immense charm and pleasure lies in its merry attitude towards such wholesale cultural borrowing. The Matrix is a giant patchwork of homages to everything from Alice in Wonderland and Hollywood film noir to 1980s cyberpunk fiction and groovy postmodern theory. In fact, the only truly up-to-the-moment aspect of this sci-fi epic is its breathtaking application of digital special effects technology. Everything else has a deliberately daggy, shopworn, throwaway aura. Why else do writer-directors Larry and Andy Wachowski (Bound, 1996) throw in – during Morpheus' solemn disquisition on "the real" – a hilariously old-fashioned television set? Or why make the black female oracle of the future's resistance troops into a no-nonsense dame dispensing gruff wisdom in her homely kitchen? The Matrix has much in common with the two most ambitious and underrated sci-fi films of recent years, Dark City (1998) and Alien Resurrection (1997). All three movies shamelessly mix lofty apparitions from art cinema (Cocteau and Tarkovsky) with trashy, futuristic plots. The Wachowski brothers add to this brew their special fondness for, and facility with, newer conventions deriving from blockbuster action cinema and Japanese anime cartoons. Neo's frankly messianic adventure is a furiously plot-driven one, so to even give away the initial moves of the story would spoil some of the unfolding fun. Suffice to say, Neo starts as Thomas, a mischievous hacker, increasingly beset in his daily life by disturbing visions and messages hailing from the underground resistance led by Morpheus. When Thomas is finally reborn as Neo, he confronts the idea that the power of The State is malefic and all-encompassing. Or is it? In a world of simulacra and simulation, all appearances are treacherous, all identities are malleable, and perhaps no one can be trusted. As in Dark City, a not entirely convincing love story (involving Carrie-Anne Moss as Trinity) promises global redemption. The Matrix walks a fine, tricky line in its frequent action sequences. If the physical world is so weightless, fluid and unreal, how can the audience believe that anything is at stake when characters face each other to exchange bullets, bombs or blows? Happily, as in the A Nightmare on Elm St series, what occurs in shadowy, virtual, dream worlds has real and lasting effects on those outmoded vessels known as human bodies. Rarely has a blockbuster been so completely enjoyable. Superbly staged and edited, it never loses its drive and intrigue. Reeves has come a long way as an actor since the woeful Johnny Mnemonic (1995) – and so has the entire cyberpunk genre on screen. The simplest props and devices of the form (such as ringing phones and blinking computer screens) acquire an urgent, poetic force. Hugo Weaving as the sinister and ubiquitous Agent Smith, with his crazy shades, accent and gestures, is a walking, talking special effect even before the digital crew sets to work on him. It is refreshing to watch this actor escape the dreary naturalism of much Australian cinema at such a frantic velocity. An evident gesture towards the continuing box-office potential of the Matrix package is contained in an open ending that begs a sequel. Or maybe that's simply another homage to Baudrillard, who wrote in "On Nihilism": "The desert is growing..." MORE The Matrix Reloaded © Adrian Martin April 1999 |

![]()