|

|

|

|

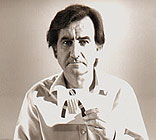

Words

and Silk: The Imaginary and Real Worlds of Gerald Murnane

|

|

|

In the Oxford Companion to Australian Film published in 1999, Philip Tyndall's Words and Silk: The Imaginary and Real Worlds of Gerald Murnane – one of my personal all-time favourite Australian films – does not rate a mention. This is sadly symptomatic of how strange, unique, unclassifiable works tend to go underground rather speedily in Australia. Nominally, the film is a documentary – even, to raise a dreaded, television-tainted term, an arts documentary, since it presents itself as a portrait of an acclaimed Australian novelist, Gerald Murnane (Tamarisk Row, The Plains, A Lifetime on Clouds, Velvet Waters). But this is far from a standard, objective view of an artist and his career – and nor is it one of those awful, mimetic exercises with corny, UK-Channel-4-style affectations, or scenes inserted between interview footage to illustrate passages from the books discussed. The subtitle of Tyndall's film – 'the imaginary and real worlds of Gerald Murnane' – announces its neat, two-part construction. The first half comprises an intense flow of images and text, giving a beautiful inventory of the key, obsessive motifs, incidents and gestures in Murnane's writing. The inventory is achronological, and quite abstract: colours, textures and shapes recur more identifiably and powerfully than people, formative experiences or primal scenes. Tyndall's intimately lush mise en scène recalls here the aesthetic of Alain Cavalier's films (Thérèse [1986], Libera Me [1993]). For me, this first part of Words and Silk goes to the heart of Murnane's work more truthfully, effectively and deeply than much of the literary commentary that work has generated. I find a lot of this commentary – about Murnane as a prose stylist, a conjurer of memories in the tradition of Proust, someone who experiments with self-conscious, stripped-back linguistic forms – rather trivial and off-the-mark. It loses touch with the centre, the real power of the writing. But Tyndall – perhaps because he, as an artist, so deeply identifies with and intuitively grasps the pulses and resonances of Murnane's prose – goes straight to this centre. There is something compulsive, obsessive, a little mad in Murnane's writing. The surface of these texts is too perfect, seamless, wound around itself too tightly. The way the sentences repeat, pile up, go over the same, solid reference points over and over – all that points to something hidden, something unsaid under everything which is so fanatically, pristinely laid out and exhibited. There are hints of a deep defensiveness, the traces of some repression or psychic self-censorship – all kinds of terrible, mysterious, sexual, violent things lurking and seething under the implacable Aussie surface of Murnane's amazing prose. If you read Murnane in a too cold, distanced or formal way, you could well imagine his view of life as objective, exterior, impersonal – a pure, stately flow of images, memories, places and dates. But finally, it is the human beings, the subjectivities in his stories, and the unspoken things that really drive them, that form the great, central mystery of Murnane's work. This fine tension between an obsessively patterned surface and what this pattern hides or only suggests is what his writing performs or stages; and it is this tension that gives his best pieces (for instance, the brilliant short story "Fingerweb") their particular power. It's a testament to Tyndall that he captures in Words and Silk this interplay of the surface and what it suggests in Murnane's work. Curiously, Tyndall's previous work, a short video documentary called Someone Looks at Something (1986), is also a portrait of an artist whose work has compulsive and secret aspects – the filmmaker's own brother, Peter Tyndall. (A special Words and Silk screening-performance event called "The Literature Club" appeared at the Experimenta festival in Melbourne in 1990, featuring Murnane and both Tyndalls.) The second half of Words and Silk focuses on Murnane himself and his real world. It deals not so much with the biographical details of the writer's life, but his very precise way of working and writing. Murnane talks directly to the camera in a very formalised, recitative way, in a highly stylised setting where the lighting, colour and space modulate and mutate – a space midway between Akerman's Histories d'Amerique (1988) and Coppola's One From the Heart (1982). The soliloquy is measured, serious as a heart attack, and utterly hypnotic. Murnane's mode of address is reminiscent of the entrancing, minimalist films of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, where (as in Fortini/Cani, 1976) people often simply read or quote a text whilst inhabiting cryptically suggestive historic locations. Gerald Murnane, as he presents himself, is like a modest but furiously noble hero from a Straub-Huillet film: he conjures his struggle with language, with words, with truth and with fiction, his way of forming and retaining images in his mind – by setting down (as he so intensely testifies) one sentence after another. This writing is like a thin red line that separates the author from the terror of some unnameable void, or chaos. Words and Silk, in its own relentless progression from frame to frame, word to word, and image to image, joins forces with Murnane's struggle to express and master that void – and it is a spellbinding spectacle. © Adrian Martin March 2000 |

![]()