|

|

|

|

Essays (book reviews) |

|

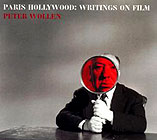

Paris Hollywood: Writings on Film |

|

|

There

was something missing from Peter Wollen’s previous collection of essays, Raiding the Icebox: Reflections on

Twentieth-Century Culture (Verso, 1993). A sharply perceptive tour through

the connecting roads of modernism, it dealt in fresh ways with great, familiar

figures and movements: Breton and surrealism, Pollock and abstract

expressionism, Debord and Situationism, Diaghilev and dance, Warhol and Pop.

But when it reached the ‘60s, the narrative broke down. The book’s final

chapters, on the project of Komar & Melamid and ‘tourist art’, were an

anticlimax. Where were the heroic figures of cinema’s new waves, like Jean-Luc Godard and Fassbinder, to carry Wollen’s densely argued account from the 1960s through

to the ‘80s?

In

a sense, Paris Hollywood is that

missing piece from the history traced in Raiding

the Icebox. Godard is here, and Hollywood, and Blade Runner. So are some grand cultural themes and obsessions that

Wollen has often addressed: architecture, speed, criminality, time, technology.

It

soon becomes clear why Wollen has saved these particular film essays up for

their own book. For, beyond adding up to a cultural history, they are also,

gently, his own, personal history: the critic who began writing for New Left Review in the early ‘60s,

played a major part in the cinema studies revolution in the late ‘60s and early

‘70s, branched into film writing (for Antonioni) and film making (with Laura Mulvey) during the ‘70s, curated art exhibitions in the ‘80s and ‘90s – ‘from

cultist to critic to theorist’, as he puts it.

Wollen’s

life as a commentator and creator begins, mythically, in Paris – at the first

public screenings of À bout de souffle in 1960 – and eventually arrives at Hollywood, or at least UCLA. In between,

film culture moves from the last gasp of innocent auteurism to the theoretical

ecstasies and agonies of semiology, and finally to the multi-media flux of

which Cultural Studies hopes to make sense.

Wollen

has been a remarkably consistent thinker. From the start – for example in Signs and Meaning in the Cinema (1969) – he oriented himself towards aesthetic theory on the one hand, and cultural

history on the other. The long view which this orientation allowed him provided

an anchor during the years in which intellectual fashions and aesthetic tastes

came and went with brutal rapidity in the academy and beyond. Wollen is not one

of those academic careerists for whom the avant-garde or psychoanalytic feminism

were In until pop culture and empiricist historicism

muscled them out. He has always pursued his interests across a vast range of

cinema – in Paris Hollywood, from

William Burroughs and Viking Eggeling to spy stories and sci fi – and never reneged his debts to formative figures like Freud, Brecht,

Eisenstein and Breton. And he has stayed aloof from certain fads, whether for

Barthes and Kristeva in the ‘60s or the current predilection for Deleuze and

Virilio. One can regret that Wollen has never quite left the Cahiers-formed cocoon of his youth –

Hitchcock and Hawks are still the touchstones, John Boorman is ‘only

incidentally modernist’ (Point Blank,

incidentally modernist?), Positif scarcely rates a mention – but one can also admire the faithfulness to principles,

and the ceaseless deepening of reflection upon them.

Wollen’s

tone as a writer is very particular, and it has led his critics down the

decades into some rude ad hominem remarks. For Robin Wood in 1975, ‘Wollen’s writing customarily suggests great haste,

as if he can only function in a flurry of excitement’ – but that excitement,

combined with ‘the air of authority and assurance, and the assumption of

impersonality, in fact combine to impose his text as definitive’. Raymond

Durgnat complained in 1982 that Wollen ‘flits from one reference to another’ in

a ‘name-salad’ that ‘can only arouse a thousand complex issues which [he] has

no possibility of properly outlining, let alone solving’. More violently, but

along the same lines, T.J. Clark and Donald Nicholson-Smith remarked in 1997

that Wollen’s ‘Michael Ignatieff authoritativeness is breathtaking’, while P.

Adams Sitney charged in 1982 that the ‘name-dropping authority he bestows upon

himself is grotesque’.

What,

in Wollen’s work, invites such rude, or at least unkind, remarks – which I, too, have committed to print in the past? A

sudden, otherwise unamplified passage from a 1968 talk reprinted in Readings and Writings: Semiotic

Counter-Strategies (Verso, 1982) suffices to give the breathlessly egghead

flavour of his early writing:

Thus Lenz, the Storm and Stress

dramatist, like Eisenstein, admired the grotesque, the Commedia dell’Arte and

caricature: of course, this grotesque strain meets with the Longinian sublime

pre-eminently in Shakespeare, the Shakespeare of the Romantics, that is, of

Garrick.

The

turning point for me as a reader of Wollen was his fine 1992 book on Singin’ in the Rain, one of the first

entries in the BFI Classics series. By this stage his style of address had

become less haughty, more elegant; the rhizome of connections between names,

movements and contexts was more patiently and generously set out. Wollen is a

remarkable historian, as Paris Hollywood also shows. The depth of his research has come to support the early intuitions

that he has always stuck to and worked at within the realm of aesthetic theory:

cinema as the inheritor of drives towards ‘composite’ form and narrative

‘cartilage’ (from Russian montage to the Hollywood musical), and the ideal of

the art work as that realm of ‘mixed codes’ which multi-media culture has made

the norm.

One

wonders why ‘London’ does not insert itself between Paris and Hollywood in the

title. For one of the most fascinating aspects of this text

is Wollen’s règlement de comptes with

his British cultural roots – a localist engagement strongly present in his life

and career (especially in his independent filmmaking), but not always evident

or reflected upon in the high-flying cosmopolitanism of his writing. In

this, Wollen embodies a typical intellectual dilemma: an embrace of exotic

traditions abroad coupled with reticence, embarrassment even, over the products

and sensibility of home. But the provocative essays here on the ‘Anglo-Austrian

entanglement’ in crime fiction, and a speculative history of British cinema in

the post ‘60s modernist era, bring Wollen firmly back home.

Wollen’s

way of approaching individual films – such as, here, Rules of the Game – is intriguing. He does not really read movies

hermeneutically, or break them down analytically (a brilliant passage in Singin’ in the Rain notwithstanding). He

approaches them historically, building up and surrounding them with their

contexts: in Renoir’s case, for example, that includes not only ‘Munich, the

failure of the General Strike and the collapse of the Popular Front’, but also

those twin avatars of modernism: radio and aviation. Neither a fetishist of

‘close reading’ nor an imposer of external, materialist grids, Wollen achieves

a rare synthesis of close-up detail and Olympian distance in Paris Hollywood.

In

an early ‘80s moment, Wollen, like many of his comrades, grappled with the not

easily reconcilable twin worlds of fiction and criticism. His solution was to

try his hand at both, and eventually to reach a provisional synthesis in the

practice of the essay form: sometimes fragmented or aphoristic, a collage of

notes, thoughts and sensations. Paris

Hollywood contains Wollen’s best work in this vein: twenty-four instances

of the mismatch in cinema, for

instance, and a splendid ‘Alphabet of Cinema’, first written as a tribute to

the legacy of Serge Daney, which here serves as an introductory map for all the

interests and encounters of the book – from Aristotle to Zorn’s Lemma, film festivals to digitality, Citizen Kane to cinephilia.

|

![]()