|

|

|

|

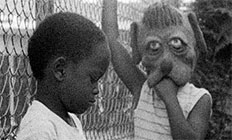

Killer of Sheep

|

|

|

Teeming

Life

Somewhere

between Several Friends (1969) and today, Charles Burnett’s work speeds

up – not (alas) in his opportunities to make work, but internally. His early

films – preeminently Killer of Sheep, today available in a superb DVD

reconstruction from Milestone – have a loose-limbed feel. The assiduous

description of everyday, ordinary lives, spacious and leisurely, in

intercrossed vignettes, takes precedence over straight-ahead narrative hooks

and resolutions. However, by the time of his acclaimed copland drama The

Glass Shield (1994), or his underrated family melodrama assignment for

Oprah Winfrey Productions The Wedding (1998), everything has become much

faster.

A

hyper-economic approach to storytelling gives rise to a breakneck speed that is

as exhilarating as it can be deliberately disorienting. A plot question left

lingering at the the end of one scene is swiftly answered in the next, with the

sound impatiently anticipating the image. (This ‘70s affectation of the audio

lead-in is disliked by many contemporary filmmakers, but Burnett is its true

poet.) Tense exchanges between characters are reduced to a shot and a

counter-shot (sometimes not even that much), a couple of lines (at best) of

dialogue, or simply a telling look or gesture.

More

than anything, Burnett grasps the task of the director as one of inventing

surprising, eloquent, forceful gestures – which is why the slow-dance scene

between the bare-chested but strangely alienated San (Henry G. Sanders) and his

wife (Kaycee Moore), trembling with amorous emotion, is the single

most-recalled moment from Killer of Sheep, or indeed Burnett’s entire,

prodigious, multi-faceted career to date.

And

this attentiveness to physical gesture – the the casual posture, the defensive

hand or arm reflex, the instinctual full-body movement of flight or embrace

(see them all, in an astonishingly swift cycle, in the devastating final scene

of The Glass Shield) – remains the same, whether Burnett is batting the

storyline slow or fast.

Rhythm,

gesture, time, space: such talk of cinematic form does not always leap to the

forefront of the minds of even Burnett’s most fervent commentators. Because so

much of his work has, for so long, stayed invisible and inaccessible, there has

always been a perceived need to return to Square One in order to plead his

case, to set right the prevailing cultural inquities, and often in a polemical

way: Burnett the great, unknown, black American filmmaker, better than Spike

Lee, his work a more authentic vision of his culture than either the Shaft or Barbershop series (that wouldn’t

be hard), an eternal, political radical pushed to the margins of mainstream

cinema and television …

Most

often, Burnett is pegged – without much further probing – as a realist, or more

tonily a neo-realist. Indeed, a glimpse at his short Quiet as Kept (2007) on the Killer of Sheep DVD – a hilarious five-and-a half-minute

sketch in which the members of a family argue over whether Star Wars, Superfly or The Cosby Show is the most suitable viewing for a black adolescent –

quickly arouses a close comparison with Mike Leigh’s quirky, slice-of-life “five-minute

movies” made for UK television in the 1980s.

But

there is more to be said about Burnett – especially as the realist designation

often serves, in practice, to replace analysis of achieved filmic form by a

nebulous praise of the auteur’s mere “powers of observation”. Alas, you won’t

get much assistance in this matter from notes by Armond White accompanying the

Milestone release. White (of the National Review) tries out all his usual

outflanking manoeuvres in this piece. He is a critic who likes to evoke a

critical mass of sickening, regressive, ignorant consensus from which he nimbly

dissociates himself, but to which he unfailingly associates his reader. This –

never a good stance for a critic in the public sphere – leads to a tiresome,

pugilistic posture.

Mr

White wheels through the predictable provocations in relation to Burnett: you’ve

only just discovered Killer of Sheep now, and missed it in ‘77? Then you

don’t really know the score! You are clambering on the current bandwagon to

hail it as a “masterpiece” (this word never comes without scare quotes, even in

the essay’s title)? Ha, you are thus castrating its true force! You want to

compare it to Umberto D (1952) or Bicycle Thieves (1948)? Rank

sentimentality! In place of all these apparent no-no’s, White proffers only one

assertion, reiterated many times: that Killer of Sheep indelibly

captures the hurt of everyday people living under oppression.

Which

is true, but not the whole story of what makes Killer of Sheep a

masterpiece (let’s drop the quote marks, please). I inadvertently prised open

one of the film’s secrets by rewatching parts of it in fast motion: Burnett is

an artist of the life of certain objects, fixtures, small loci or

transition-points – like a car, or a front porch. His characters teem in, out,

through and around these special points, subject to a dozen tiny but forceful

determinations: the time of day (leaving for work or returning home), each

person’s highly individual style and rhythm, and the intersubjective dynamics

of friends or family.

One

of the best accounts of Killer of Sheep could have been inserted into

Gilles Deleuze’s books on The Movement-Image and The Time-Image in the 1980s, if only the French philosopher had been able to see it in Paris

at the time: Burnett’s cinematic poetry arises from the hundred small “sensory-motor

disconnections” of every damn day, gaps and disclocations from which a sad but

resilient emotion flows.

Burnett’s

style – in those early years, as well as in shorts like Quiet as Kept and the superb When It Rains (1986) – is as profoundly musical as that

of Martin Scorsese or Terrence Malick. This is another aspect of Burnett’s work

that deserves close attention: the superbly placed snatches of music, the

mixing of that music with the rhythms, intonations and cadences of the spoken

words, the way that the scenes seem to be shaped to the music, rather than (as

is usual) vice versa.

Indeed,

when we look again closely at that famous dance scene in Killer of Sheep we notice, alongside the exactness and intensity of the human gestures, how

music washes in and out of the tableau, like the ebb and flow of life itself:

strangely but beautifully, when the first song is over, another begins, after

the bodies have parted, doubling the sadness and wisdom of the scene.

In

his magnum opus The Body of Cinema (2011), Raymond Bellour defined the

peculiar emotion that emanates from special moments of film. He emphasises,

more than even in his stricter semotic days of 1970s textual analysis, the shot

as the cinematic unit par excellence. The shot, he argues, contains, marshalls and

sends in various directions the emotions that are created and sustained by the

smallest, frame-by-frame movements in cinema: the beating wing of a bird, the

splutter of a car engine, the discontinuous landscape seen through a train

window, as well as all the movements and gestures of the human body. It’s at

that level, finally, that we will come to appreciate the great artistry of

Charles Burnett.

For more on Killer of Sheep, its critical and scholarly reception, and especially its central dance scene, see the 2015 audiovisual essay by Cristina Álvarez López and me, Against the Real.

|

![]()