|

|

|

|

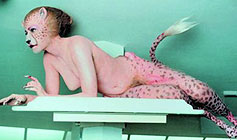

The Cremaster Cycle

|

|

|

I sat through all five parts and seven hours of Matthew Barney’s The Cremaster Cycle, largely out of a sense of duty to alternative forms of cinema, and admiration for the distributor bold enough to acquire and showcase such difficult, image-driven, non-narrative work for Australia.

But

the international fame of Barney’s so-called ‘epic masterwork’ rests far too

much on such cultural good will. So now it is time for me to put aside my

allegiance to the cause of non-mainstream film and ask squarely: is The Cremaster Cycle actually any good?

Hybrid

works that exist in the fuzzy area between the gallery and the movie theatre

tend to be treated with vast indulgence and granted special dispensation: they

are evaluated neither as art nor cinema. But The Cremaster Cycle, it seems to me, fails spectacularly both as

art and as cinema.

One

cannot judge this art without judging the artist. Heaven knows, Barney presents

himself as the supra-auteur of all that we see and hear. Like many of his

contemporaries, he turns narcissism and exhibitionism into the very principle

of a performance-based art that places his own ‘body in question’.

This

means that we must watch Barney, in every conceivable permutation of costume

and make-up, tap dancing, climbing walls, crawling through tunnels, diving into

the ocean, and much more. Unfortunately, he is one of the least appealing

presences in the entire history of the moving image, and thus a rather

imperfect hook on which to hang seven hours of celluloid.

Barney

can be fairly taken as an embodiment of everything that is wrong in modern art.

Firstly, there is the grand folly of hoping to sustain a series over many years

(in this case, ten), grimly sticking to ideas and motifs sketched at the

outset. This can be done, but Barney is no Marcel Proust. His ‘cycle’ plods

through its levels and stages, instalment by instalment, with a bland,

relentless determination that makes for joyless viewing.

Secondly,

there is the not small matter of the quality of those ideas and motifs. Barney

bases the Cremaster films on an

enormous conceit regarding the biological ‘life force’ as it struggles its way

into being. As a whole, the cycle plays like an over-extended version of the

‘Dawn of Man’ prologue in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

But

at least Kubrick took us on a gripping and entertaining ride through the

cosmos. Barney lazily plays the card that so much contemporary art does, hoping

that some vague gesture in the direction of science, chemistry, biology or

mathematics will be enough to impart a weighty, fundamental significance to the

woolliest spectacle.

Hip

art critics are keen to tell us that Barney’s work addresses the processes of

‘sexual differentiation’, which makes it sound very political. But why does he

then base the entire project around a celebration of the “male cremaster muscle

which controls testicular contractions” – setting endless images of masculine

striving against complementary images of women as liquid pools which surround

and dissolve the master-male who is always played by Barney himself?

If

this is the best gender politics that supposedly advanced modern art is capable

of, then we are all in deep trouble.

Thirdly,

we come to the readability of any of this as it passes before us on screen. To

put it bluntly, The Cremaster Cycle marks the absolute triumph of the art catalogue. It is impossible to follow or

understand most of what happens without a close consultation of the

accompanying, explanatory notes. The work itself is cryptic to the point of

total incomprehensibility – which may well be why it tricks so many art fans

into a state of quasi-religious devotion.

At

the same time, Barney’s cryptic way with storytelling and concept-building is

married to an over-cultivated weakness for supposedly primal symbols. Certain

biological diagrams become the artist’s obsessive graphic motifs, while a

barrage of nature metaphors (fire, ice, honey, flood)

is used to plug any yawning intellectual gap.

So

that’s the bad art quotient. What about the cinema quotient? Barney has said in

an interview that he is “more interested in problems of sculpture than problems

of cinema”, and you would be well advised to take that as a warning. The Cremaster Cycle is based on a single

cinematic device, primitive enough to remind us of film’s earliest days:

alternation.

Cremaster 4, the first to be shot

back in 1994, sets the pattern: Barney’s tap routine is intercut with

colour-coded motorcycle teams burning around the Isle of Man. The piece goes

back and forth so repetitively that we soon want to scream. In every part of

the cycle, something finally does happen – but Barney gives the kiss of death

to that time-honoured technique of cinematic suspense and intrigue known as the slow burn.

Such

‘problems of cinema’ should have concerned Barney a little more, especially

after so many years of trotting out the same alternating template. Cremaster 5 (1997), a lush, operatic

piece featuring a game Ursula Andress (one of several celebrities featured

across the series) shows how completely clueless Barney is when it comes to

energising space, time, sound and image in a truly filmic way.

Cremaster 1 (1995) – in which

Goodyear blimps hover over a sports stadium – is the funniest and most successful

of the series, but it too takes a cute idea and slaughters it through dull

repetition.

Cremaster 2 (1999) is the most

ambitious and serious film of the cycle. It is also easily the least

comprehensible and the most pretentious. Early on, images and sounds worthy of

David Cronenberg or David Lynch – such as the brilliantly orchestrated aural

contest between a heavy metal drummer and a swarm of bees – make an indelible

mark.

But

by the time, an hour later, that we arrive at a pleasant image of old-time

dancers which is meant (according to the program notes) to symbolise real-life

killer Gary Gilmore’s “chronological two-step that would return him to the

space of his alleged grandfather, Houdini”, we realise how weak this piece is

at articulating its wildly diverse elements.

Cremaster 3 (2002), which includes a

long section called “The Order” apparently designed to sum up the whole cycle,

is no less grand in its scope. But it depends heavily on Barney’s facile, camp

humour – proving once and for all that, in modern performance art, the only

things that people understand are the jokes. If that.

Finally,

what is there to see in The Cremaster

Cycle? The much-vaunted ‘fusion’ of art, cinema, theatre,

music, design, fashion and celebrity? Wagner must be turning in his

grave at this mangled incarnation of his dream of a ‘total art form’ merging

all means of aesthetic expression. In fact, as in so much multi-media,

inter-disciplinary art, each component suffers in the haste and sloppiness with

which the grand ensemble is glued together.

Some

will argue that Barney’s work is best taken as pure spectacle for our

dislocated, postmodern age. If so, I believe there is more fun to be had

channel surfing during an average night on television. But it must be conceded:

as a cultural event, The Cremaster Cycle is a once-in-a-lifetime experience. At least, I

sincerely hope so.

MORE artist's movies:The Ghost Paintings, Feeling Sexy © Adrian Martin February 2004 |

![]()